This post was originally published on this site

Lana Linge has $42,000 in credit-card debt, but it’s not the giant tab that has her most frustrated.

The 29-year-old says she takes full responsibility for her debt. After getting her first credit card in her early 20s, Linge accumulated small amounts of debt but was always able to pay it off. That changed in 2020: Linge struggled with managing her spending on necessities and other items, like clothes, while in isolation, causing her bills to grow. Things got worse after she lost her job this past October, and she eventually depleted her savings to keep up with the payments on her card.

“I know for a lot of people, they’re in debt because of these freak things that are outside of their control,” Linge tells me. “The reason that I’m in debt primarily is from overspending, and I don’t try and negate that in any way.”

iStock image

Overwhelmed, Linge is going through the painful bankruptcy process to discharge the debt. Looking back, she regrets not paying more attention to the details of her card’s interest rate. Wooed by the rewards and perks the companies were offering, Linge signed up for a card with an interest rate she says ballooned to over 20%. While Linge no longer has access to her financial records due to the bankruptcy, she told me that in recent years most of her debt load was attributable to accumulating interest. The growing interest payments meant that even as she worked to get her spending under control, the bills kept growing.

Linge’s experience may be on the extreme end of America’s personal finance journeys, but she isn’t alone in her interest-rate woes. Consumers are always looking for deals, and it’s easy to be swayed by credit-card companies offering glitzy rewards and points. As Adam Rust, the director of financial services at the Consumer Federation of America, told me, issuers are “putting the sizzle before the steak.” But many of these cards come with high rates and hidden fees, and by the time consumers realize just what they signed up for, credit-card companies have raked in the profits.

“Credit-card companies can get away with charging high rates of interest because consumers aren’t necessarily paying attention and marketing doesn’t focus on that,” he said.

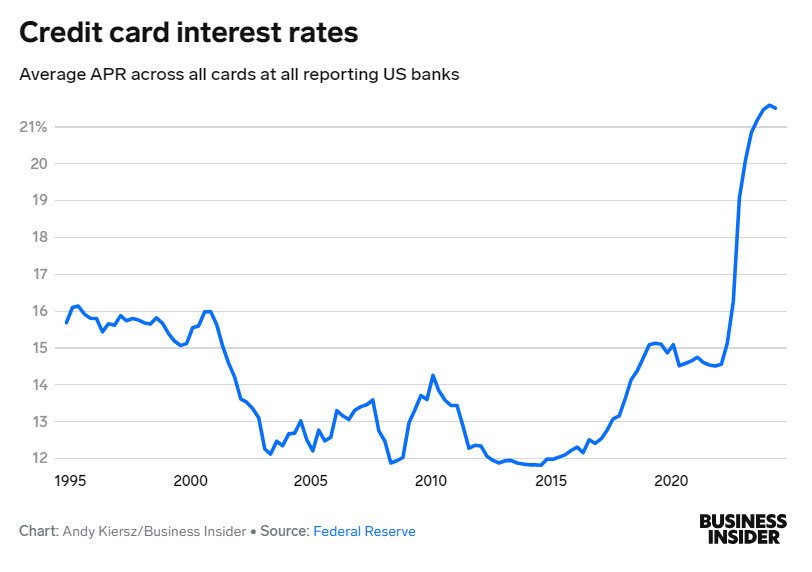

The average credit-card interest rate is now just over 21%, up from about 15% a decade ago. More importantly, the gap between the interest rate that credit-card companies pay banks that oversee their business and the one they charge you is the widest it has been in nearly 30 years. Even with existing regulations and the recent interest-rate cuts from the Federal Reserve, credit-card companies have the power to exploit consumers, and people with growing debt piles have few avenues for relief. Additionally, as credit-card companies continue to charge high interest rates, more cardholders in debt become delinquent — and that could push the US economy closer to recession.

“What we’re seeing from the data shows a rapidly deteriorating financial landscape for Americans,” Bruce McClary, a senior vice president at the National Foundation for Credit Counseling, tells me, “with a lot of people teetering on the brink of severe financial crisis.”

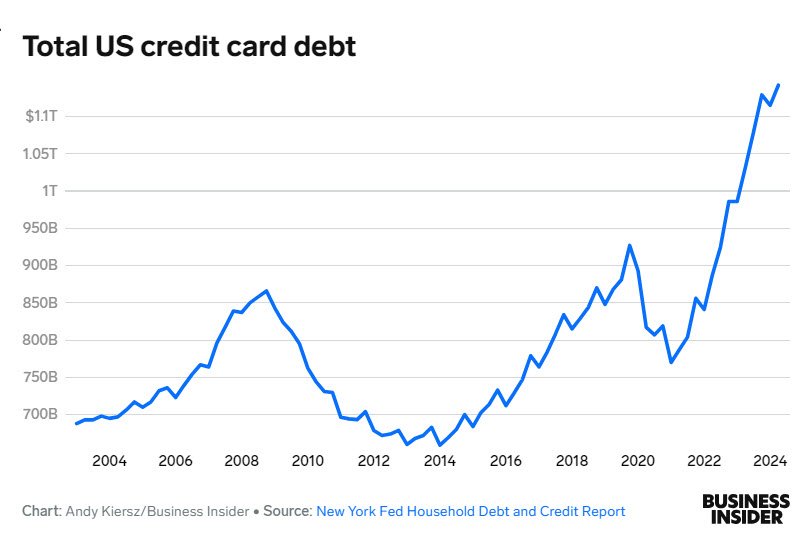

The squeeze is on

Americans have a lot of debt piled up on their little pieces of plastic. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York said in August that Americans owed a record $1.14 trillion on their credit cards in the second quarter and that balances increased by $27 billion from the same period a year ago, a 5.8% jump. TransUnion says the average credit-card balance per debtor stands at $6,329, up by 4.8% from a year ago. Most worryingly, according to the New York Fed, the percentage of people who had fallen more than 90 days behind on their payments climbed to 6.4% by the end of 2023, up from 4% at the end of 2022. Austan Goolsbee, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, described those rising delinquencies as “uncomfortably high” and a “warning sign” for the economy.

This may be worrying news for average households and the US economy, but it is wonderful news for the credit-card companies. Credit-card issuers make money in a few ways, but one of the most important is interest payments. When a customer doesn’t pay off their full balance each month, they pay interest that the credit-card company collects, so increasing interest rates is an easy way to bring in more profit.

Credit-card companies are making so much money.

To better understand the strength of the credit-card industry, look at the split between the federal funds rate — the interest rate at which banks make very short-term loans to each other, which is also used as the benchmark for almost every other type of loan — and the average credit-card interest rate. Data from the St. Louis Federal Reserve indicates the difference between the rates is at a nearly three-decade high, suggesting credit-card companies feel free to charge high interest rates regardless of what the Federal Reserve does with the federal funds rate.

“We should never lose sight of just how profitable credit cards are,” Rust says. “You’ve got interest, you’ve got interchange, you’ve got late fees; credit-card companies are making so much money.”

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau estimated in February that major credit-card companies earned about $25 billion in additional interest revenue in 2023 by raising their annual-percentage-rate margins, or the difference between the APR and the interest rate set by banks, known as the prime rate. It also found that major issuers raised the average margin by 4.3 percentage points over the past decade, to an all-time high. Using data on how Americans deploy their cards to paint a representative picture, the CFPB estimated that the margin increase cost the average consumer with a balance of $5,300 more than $250 in 2023. On top of that, the bureau’s 2023 report to Congress on the credit-card market said companies charged consumers over $105 billion in interest in 2022, helping boost the profit margin for these companies to 5.9% from 4.5% in 2019.

These staggering numbers are made possible by the tactics that credit-card companies use to lure in new customers. Antoinette Schoar, an economist at MIT who coauthored a paper examining credit-card companies’ use of behavioral biases to acquire customers, says companies use data to determine a prospective customer’s education and income levels and will tend to offer products with hidden fees and high rates to people with lower educational attainment and income. For example, a company might advertise a 0% APR, but the consumer might not realize that that rate can’t last forever, leading them to take on balances higher than they can afford to pay off. She says that while the tactics companies use to appeal to certain consumers can lead to high balances and credit-card debt, the companies aren’t the only ones to blame — government regulations to prevent this kind of misleading marketing by credit-card companies could force the companies to compete by offering customers a better deal.

“We need better regulation so that the card companies are competing on the right dimensions and not on increasing convolution or increasing confusion to their customers,” Schoar says.

‘The highest credit-card rates we’ve ever seen’

Until 1978, most states had laws capping interest rates for credit cards and consumer products. But a Supreme Court decision that year allowed banks to charge whatever interest rate they wanted if they were headquartered in a state without a usury law. This inspired a race to the bottom, with states like South Dakota and Delaware doing away with their laws in order to attract more business from banks. The industry ended up with, as David Silberman, a senior fellow for the Center for Responsible Lending, put it, virtually “no legal constraints on the interest rate they charge.” Lawmakers have tried to rein in the industry — for instance, the CARD Act, enacted in 2009, required card issuers to notify consumers of interest-rate increases at least 45 days in advance and put restrictions on things like late fees and withdrawal fees. The legislation, however, didn’t cap interest rates or rate increases.

Lowering the current high interest rates, and the profits that come with them, has become a priority across the aisle. GOP Sen. Josh Hawley introduced a bill in 2023 that would cap interest rates at 18% and impose penalties on companies that violate the cap. “Americans are being crushed under the weight of record credit card debt—and the biggest banks are just getting richer,” Hawley said in a statement, adding that “capping the maximum credit card interest rate is fair, common-sense, and gives the working class a chance.” Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren brought up the issue during a Senate hearing in May, saying credit-card companies had “grown their profits through interest and fees.”

The Federal Reserve cut its benchmark interest rate in September after holding it steady for over a year, but credit-card holders with high interest rates won’t feel any relief off the bat. Michele Raneri, a vice president and head of US research and consulting at TransUnion, told me that’s because consumers have to pay off their balances at the interest rate in place when they accumulated the debt, so the lower rate wouldn’t apply.

“It’ll take a while for the consumer to realize the benefit of it,” Ranieri says.

The high inflation of the past few years has also made it easier for consumers to fall into credit-card debt. Ted Rossman, a senior industry analyst at Bankrate, described the feedback loop of high prices and high interest rates as “a tough cycle to break.” Credit-card companies know what they need to do to maximize profit: If they offer rewards and bonuses up front, they can snag new customers before they realize the high rates they’re signing up for. Profits keep rolling in for issuers, while consumers fall further behind.