This post was originally published on this site

‘Fomo’ is powering today’s frothy asset prices — but the fear of loss may be about to take over.

iStock-1836618676

The behaviour of equity markets over the course of this extraordinary year has come close to matching the dictionary definition of levitation. The Trump trade war, spiralling fiscal deficits and public debt, pervasive geopolitical risk, the radical dismantling of the postwar international order, declining global growth prospects — all have failed to hold back the magical rebound after investors’ initial panic in April over Donald Trump’s erratic on-off tariff tantrum.

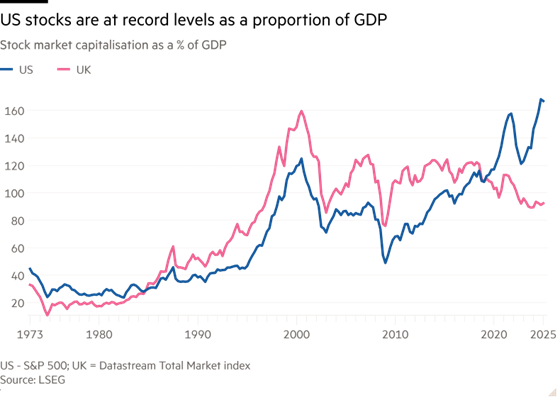

Applying the yardstick that investment sage Warren Buffett regards as the best single measure of market valuation — stock market capitalisation relative to GDP — US equities are at historic record levels. The UK market has lagged behind the US on the GDP-ratio but the FTSE 100 index has nonetheless ventured into record high territory, while other developed world markets have proved surprisingly resilient.

In the face of another Trump tariff deadline on August 1, battle-hardened markets seem more vulnerable to a modest fit of the vapours than abject capitulation in response to this new test of nerves.

How, then, to explain the growing insouciance of investors this year towards headwinds that measure a full 12 on the Beaufort scale?

At one level this gravity defiance has been about the “Taco” phenomenon; short for Trump Always Chickens Out, the brilliant abbreviation coined by the FT’s Rob Armstrong to explain investors’ willingness to shrug off the tariff threat.

But, at a more fundamental level, markets are preoccupied with the next stage of the digital revolution. Nobody really knows how artificial intelligence will affect the world but there is a widespread perception that it will utterly transform the functioning of labour and capital, revolutionise the nature of work and even redefine what it means to be human, thus providing unimaginable rocket fuel for corporate profits and equity market valuations. Or so techno optimists think, oblivious to daunting potential cost implications.

This is the stuff of incipient bubble euphoria, as portrayed in Extraordinary Popular Delusions & The Madness of Crowds by 19th century author Charles Mackay. Optimism about such revolutionary changes spurs excessive risk taking and borrowing as herd behaviour drives an accelerating stock market bandwagon.

Sure enough, recent market buoyancy has been driven by furious buying of US tech stocks which, among other things, has pushed chipmaker Nvidia’s market capitalisation to a world record $4tn-plus. Froth is everywhere. Excess liquidity in the system has spawned frenetic crypto speculation and growing use of crypto as collateral for lending and much else besides.

At the same time, companies, including the Trump family’s media firm, are stockpiling crypto assets, aiming to monetise the president’s promise to make the US “the crypto capital of the world” and cash in on the mainstreaming of this highly speculative alternative asset. Note, too, that Mira Murati, the former Open AI chief technology officer, has raised large sums for her Thinking Machines Lab, an AI start-up, that is revealing very little about what it is working on. That carries a striking echo of the infamous 18th century bubble-era flotation described by Charles Mackay whose prospectus trumpeted: “A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.”

That could equally serve as a description of the current blank cheque Spac phenomenon, where special purpose acquisition companies are formed to raise money through initial public offerings with a view to buying unspecified existing listed companies. The Trump media outfit came to market via the boom time Spac short-cut.

All this makes a nonsense of that staple of economic textbooks, the efficient market hypothesis, which asserts, broadly speaking, that the market is always correctly priced. More plausibly, economists seek to rationalise such speculative behaviour by relating asset prices to risk, which they equate with volatility.

Yet this definition of risk is not particularly helpful to mere mortals. Perhaps the old Wall Street adage that markets are driven by fear and greed may be nearer the mark — at least when it comes to fear. As Howard Marks, co-founder of Oaktree Capital Management, has put it: “I don’t think most investors fear volatility. In fact, I’ve never heard anyone say, ‘The prospective return isn’t high enough to warrant bearing all that volatility.’ What they fear is the possibility of permanent loss.”

In the aftermath of a bubble the losses can be awesome. In UBS’s latest Global Investment Returns Yearbook, Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton estimate that the dotcom crash that began in March 2000 inflicted a UK market loss on investors in real terms of 49 per cent. It took until October 2006 for them to recoup their losses. Then, between June 2007 and March 2009 after the preceding credit bubble and the great financial crisis, UK equities fell again by 47 per cent in real terms.

Yet the salutary experience of these huge losses appears now to have been consigned to the back burner. That said, a different kind of fear is at work, namely the fear of missing out, or Fomo.

When this term first emerged in the mid-2000s it was used by clinicians to describe something that was happening on social media where young people, bombarded with images of the successes of their peers, became anxious that everyone else was having more fun than they were.

The clinical view of Fomo, with its emphasis on social contagion, readily migrates to the stock market context. Indeed, financial history is full of examples of precisely this kind of fear, not least in the case of Isaac Newton, the great astronomer, physicist and Master of the Mint, during the South Sea Bubble. The economic historian Charles Kindleberger recounts, in his book Manias, Panics and Crashes, how Newton sold out of his shares in the South Sea Company at a solid 100 per cent profit of £7,000 only to be infected months later by the general mania, as he observed the stunning profits earned by others. He re-entered the market at the top for a larger amount and ended up losing £20,000, or around £3.6mn in today’s money.

There are now signs that the intellectual climate is changing in relation to risk. This is reflected in a recent paper by Rob Arnott and Edward McQuarrie which highlights empirical evidence that risk alone fails to capture the messiness of human emotions in markets and that reward correlates only weakly and at times not at all with risk. In an ambitious attempt to replace risk theory with fear theory, they suggest that fear of missing out (Fomo) and fear of loss (Fol) are the dominant emotional drivers for investment behaviour. Their thinking also minimises the role of greed, which would have struck a chord with Warren Buffett’s late partner Charlie Munger, who once remarked in a distinctly Fomo mode that “the world is not driven by greed. It’s driven by envy”.

The paper argues, among other things, that fear is an appropriate response when investors face radical uncertainty rather than probabilistic uncertainty that can readily be quantified using metrics such as standard deviation. This fear, Arnott and McQuarrie say, becomes palpable when a narrative of revolutionary change takes hold, as with dotcoms and artificial intelligence. Stocks with low valuation multiples and small market caps, they add, may still be shunned by investors who fear they are missing out on some seemingly low-risk, super-innovative sure thing.

Note, at this point, that those who succumb to Fomo are not invariably foolish. One factor that can inspire the syndrome is a worry that a window in the markets may be closing, thereby shrinking profitable investment opportunities. Consider the private markets. Howard Marks’s Oaktree Capital Management pursued a business model in the post-crisis period of ultra-low interest rates built on accepting and managing credit risk in private markets.

Part of the rationale was that at times when retail money plays a significant part in driving up asset prices in public markets, returns on those assets are subject to downward pressure. So one of the attractions for Oaktree in private credit was that mutual funds and exchange traded funds played little or no part in these markets, leaving an attractive illiquidity premium available to be harvested by expert investors.

That has now changed. Big global asset managers are busily channelling retail money into collective private market investment vehicles, which means that a window is indeed coming down on opportunities to reap an illiquidity premium in private equity or private credit.

This reflects interestingly on initiatives of UK chancellor Rachel Reeves to press British pension funds to increase their exposure to more risky, illiquid private markets. As Howard Marks put it, we often hear that riskier investments produce higher returns and if you want to make more money, take more risk. Yet both formulations are terrible because if riskier investments could be counted on to produce higher returns, they wouldn’t be riskier.

Here, in short, is a striking example of government encouraging procyclical investment just when the supposedly attractive illiquidity premium has already started to shrink.

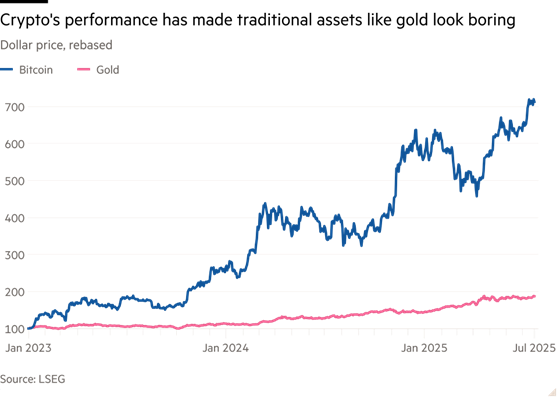

The most explosive current instance of Fomo relates to another closing window. The value of global crypto assets reached $4tn for the first time this month as speculators anticipated a deluge of money into the sector in response to new US digital asset legislation. That number again. Crypto’s achievement is astonishing given that it is devoid of intrinsic value and its contribution to the productive economy is minimal compared to that of Nvidia et al. Its chief utility appears to be to enable payments by criminals and to scammers, while gratifying the urges of gung-ho speculators. It is striking that crypto’s performance has even made gold, the traditional if volatile bolt hole for nervous money in dangerous times, look boring.

Surely, you ask, the imprimatur of the US government and Trump’s commitment to build a strategic national bitcoin stockpile should provide underpinning for this otherwise fragile asset? Not if history is our guide. The great 18th century Mississippi bubble, initiated by the Scottish economic theorist and gambler John Law, obtained exclusive rights to develop land in French-owned Louisiana, along with monopoly rights over the French tobacco and slave trades. Law’s company even took over the collection of French taxes and management of the note issue — all with the backing of the French regent, the Duke of Orléans. Fomo fuelled the bubble until the whole edifice imploded spectacularly in 1720 amid rip-roaring inflation and spiralling government debt.

Crypto enthusiasts argue that the stablecoin version of crypto is now fit for inclusion in mainstream portfolios because, in addition to the new legal framework, it is backed by solid value in the shape of bank deposits, US Treasury securities and corporate bonds or loans. Yet, the price of the backing assets can fluctuate. And as economists Yiming Ma, Yao Zeng and Anthony Lee Zhang point out in a recent University of Chicago paper, stablecoins are vulnerable to panic runs similar to bank runs because they hold illiquid assets while promising a fixed redemption value.

Veteran market observer and former bond trader Antony Peters warns against ignoring the old City adage that investors should never forget that the door marked “Entrance” is always larger than the one marked “Exit” and that the disproportionality is reflected in the promised juiciness of the investment’s return. Quite so.

What, then, should investors do to counteract these overwhelming fearful instincts? First, identify where, in the recurring oscillation between Fol and Fomo, we stand and what are the risks of a crash in a future grinding transition from Fomo to Fol. In my judgment, while a financial crisis will emerge in due course it is not necessarily imminent. The problem is rather that at today’s heady valuations investors are taking on a degree of risk that will not be rewarded by a commensurate risk premium.

That means that portfolio diversification is vital and there is a strong case for increasing exposure to boring assets, not least cash which has resumed yielding a real income after allowing for inflation. But leave it to madcap gamblers, money launderers and fraudsters to diversify into crypto. Yes, you will miss out for a while in today’s manic pro-crypto climate. But in due course the crypto losses will be crushing.

© 2025 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.