This post was originally published on this site

Is there a better gauge of a nation’s strength than the vitality of its businesses? Thriving enterprises are a source of wealth and power, drivers of job creation, foundries for new technologies, and a sign that the institutions of education, finance, law and politics are working as they should.

So, eight years after Donald Trump won the White House with a bleak vision of a US in decline, four years since the Covid-19 pandemic tested national resilience and two years since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine rolled the iron dice(1), it’s striking that America’s biggest businesses are doing better than ever.

Photographer: Ian Shiver for Bloomberg Businessweek

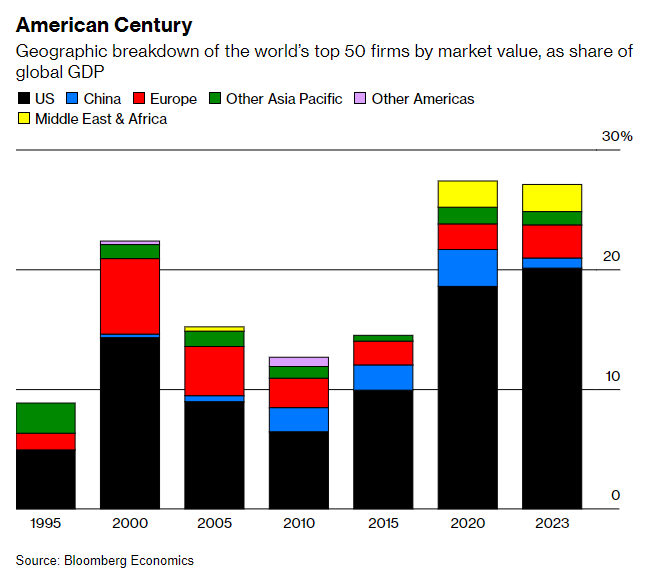

In 2023, American companies claimed 32 of the top spots in a ranking of the 50 largest publicly traded firms by market capitalization. That’s the highest number in data going back to 1995. Their dominance is even more stark when you consider that by market value, made-in-the-USA firms accounted for 74% of the total; made-in-China companies—America’s nearest rival for global supremacy—took only 3%.

Why the divergence? Part of it is strength at home. An unrivaled innovation ecosystem, deep and liquid capital markets, a nation-of-immigrants work ethic, and pro-business taxes and regulations continue to produce winners. Nvidia Corp., whose chips are powering the artificial intelligence revolution, is the latest example.

Weakness abroad is also part of the picture. China’s crackdown on its own entrepreneurs, billed as part of President Xi Jinping’s campaign to promote “common prosperity,” is a self-inflicted wound. India’s conglomerates are hobbled by weak governance, as evidenced by the stream of corporate scandals. In Europe, fragmented national markets, high taxes and onerous regulations are stumbling blocks to global competitiveness.

If the world is entering a period of struggle between democracy and dictatorship, free markets and state control, having the most powerful businesses is both a substantial source of strength for Team USA and a powerful symbol of the virtues of a democratic, free-market system. Another positive: With 58% of Americans owning stocks, the financial gains touch a broad swath of society.

Before breaking out the ticker tape and commencing a celebratory reading of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin(2), it’s worth asking a question. In 1953, responding to concerns about whether he would use his new position as secretary of defense to benefit his former employer, General Motors Co., Charlie Wilson told members of Congress, “What’s good for GM is good for America(3).”

Even in an era of chrome-plated optimism about corporate success and middle-class prosperity, Wilson’s answer appeared over the top. Seven decades later, with corporate profits booming and middle-class incomes stagnating, questions about the alignment between business interest and the public good run even deeper.

Size is part of the problem. In 1995 the market cap of the world’s top 50 firms equaled about 9% of global gross domestic product. By 2023 that number had risen to 27%. The Founding Fathers recognized the risks in that concentration of corporate power. Thomas Jefferson hoped to “crush” the “aristocracy of moneyed corporations” before they “challenge our government to a trial of strength.”

Sure enough, the evidence suggests today’s corporate aristocrats are busy squeezing workers, greedflating prices, minimizing taxes and bending politicians to their will. In 1995 the top 50 global firms paid a median effective tax rate of about 35% and had a profit margin of 6%. By 2023 the effective tax rate had fallen to 20%—reflecting the growing use of offshore tax havens—and the profit margin had risen to 20%.

With a portion of those profits, big businesses buy influence over government policy. In the US, they recently scored a major win. The Supreme Court’s decision at the end of June to strike down what’s known as the Chevron doctrine(4) significantly reduces the scope for such regulators as the Environmental Protection Agency to make rules—tipping the scales in Jefferson’s “trial of strength” further toward corporations.

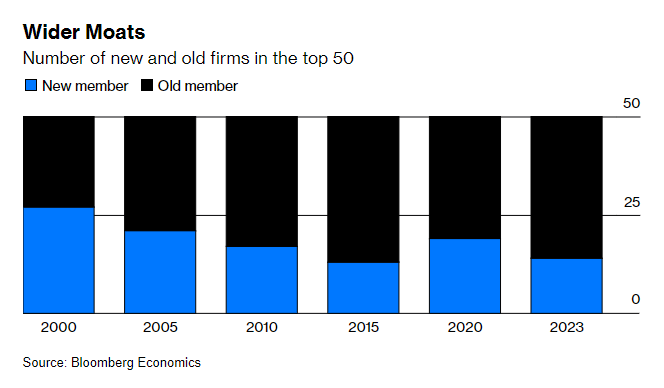

Enormous size also means protection against competition. Warren Buffett, whose Berkshire Hathaway Inc. occupies the ninth spot in the ranking, talks about the importance of a “moat” to protect corporate castles from invaders. Moats appear to be getting wider: In 2000 some 27 of the companies on the top 50 list were new entrants. In 2023 that number was only 14.

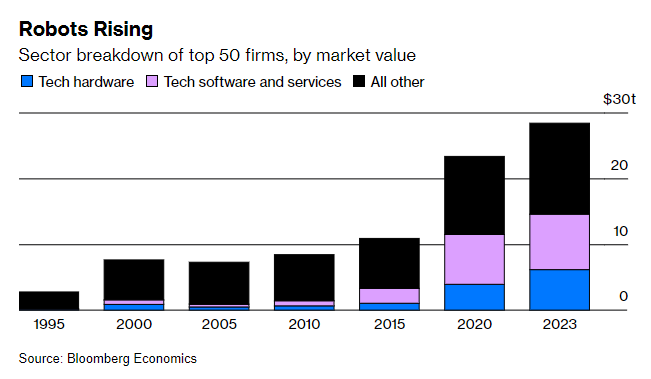

The growing importance of the tech industry also changes the dynamic between business and the national interest. In 1995 tech companies contributed 8% of market cap for the top 50 firms. In 2023 that share was 51%. Part of the reason for that rapid rise is their single-minded pursuit of corporate interests, even when those are at odds with national priorities.

Examples aren’t hard to find. Apple Inc. reportedly inked a secret $275 billion deal with the Chinese government promising to play a role in developing the country’s economy and technology. Back in the days when Facebook still hoped for China market access, Mark Zuckerberg asked President Xi to name his unborn baby. Semiconductor firms complying with the letter but not the spirit of sanctions have forced US regulators into a game of whack-a-mole to prevent China getting its hands on advanced AI chips.

The efforts of the US to block China’s AI ambitions highlight another question. The rise of reasoning robots will certainly be good for real-world versions of The Terminator’s Cyberdyne Systems, the fictional business that churns out cybernetic assassins. Will it be good for everybody else? The answer depends on whether AI is a complement to human workers, boosting their productivity, or a substitute, throwing white-collar workers into unemployment in the same way factory automation did to their blue-collar brethren.

The second industrial revolution, which brought innovations including Henry Ford’s production line and Thomas Edison’s lightbulb, boosted corporate profits and workers’ wages at the same time. In an optimistic scenario, the AI revolution follows the same trajectory.

That outcome is far from guaranteed. As Massachusetts Institute of Technology economists Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson demonstrate in their 2023 book, Power and Progress, in the grand sweep of history, advances in technology are positive for prosperity. Yet in the span of years and decades over which lives are lived, the losers often outnumber the winners.

The first industrial revolution made factory owners rich, but it took decades for workers to share in the gains. As Acemoglu and Johnson document, the arrival of power looms at the start of the 19th century decimated employment among Britain’s handloom weavers, whose real wages fell by more than half. The AI revolution might follow the same pattern. A study that the International Monetary Fund published in January found that about 30% of jobs in advanced economies may be in jeopardy.

The risk is we’re all handloom weavers now. If that’s the case, the stock boom for America’s AI champions is—in part—a bet against the interests of a generation of American workers.

***

- “If the iron dice must roll, may God help us,” said German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg in a 1914 speech.

- Forbes magazine once described the most entrepreneurial of the Founding Fathers as the “Colonial amalgam of Warren Buffett, Steve Jobs, and Bill Gates.”

- Wilson was more equivocal than the public memory suggests. What he told Congress was this: “For years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.”

- An administrative law principle established by a 1984 Supreme Court ruling that compelled federal courts to defer to a federal agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute.

Tom Orlik is the chief economist for Bloomberg Economics. He’s the author of “Understanding China’s Economic Indicators” – a guide to China’s economic data. He is based in Washington DC., following more than a decade in Beijing.

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.